Nature Neuroscience paper: “Oscillatory dynamics coordinating human frontal networks in support of goal maintenance

August 3, 2015 by Bradley Voytek

Phew! One of my post-doc papers is finally out in Nature Neuroscience, "Oscillatory dynamics coordinating human frontal networks in support of goal maintenance" (link). (Parenthetical: if this kind of thing interests you, feel free to drop me an email and/or drop by my lab's posters at SfN (PDF)!)I can't begin to express, within the constraints of my literary ability, how happy I am to see this paper published. It's been a long time in the making. Seriously this paper is older than both of my children. (Although, having two kids is a part of what delayed this paper; I took a lot of time off when they were each born and the concomitant lack of sleep impaired my cognition something fierce.)

The genesis for this paper was borne out of ideas from co-authors David Badre and Andy Kayser, along with my post-doc mentor Mark D'Esposito. Those three have published heavily on a hierarchical organization of the frontal lobe, which, to quote from that paper, states that:

Progressively rostral [anterior; toward the front] frontal lobe regions seem capable of supporting increasingly abstract neural representations and complex action rules. Such a differentiation would be essential in a hierarchical system, where ‘higher’ levels must maintain their state independent of the state of lower level processors or moment-to-moment changes in the environment.They wanted to test this using invasive electrophysiological recordings in humans (known as "ECoG", from "electrocorticography") to see if they could observe the relative timing of neural activity in different frontal sub-regions. Because of my previous frontal lobe (1, 2) and ECoG (1, 2) work, this matched my interests nicely and I came on board to analyze the data.

Initially my goal was to replicate the previous work that had been done in fMRI and lesion experiments by looking at the magnitude of the high gamma response across different frontal lobe sub-regions. We care about this "high gamma" activity (which is electrophysiological activity above around 80 Hz or so) because it's a strong correlate of local neuronal population spiking activity (1, 2), but it's really best detected not in scalp EEG, but invasively under the skull (see my strangest paper ever). Essentially if the population under the ECoG electrode is more active, high gamma is higher.

Ultimately we had ECoG data from four participants, each of whom did a variant of the Badre tasks simplified to accommodate the limitations of the ECoG recording environment (remember, these people had just undergone brain surgery mere days beforehand). The version of the task used here consisted of four trial conditions, parametrically increasing in task abstraction.

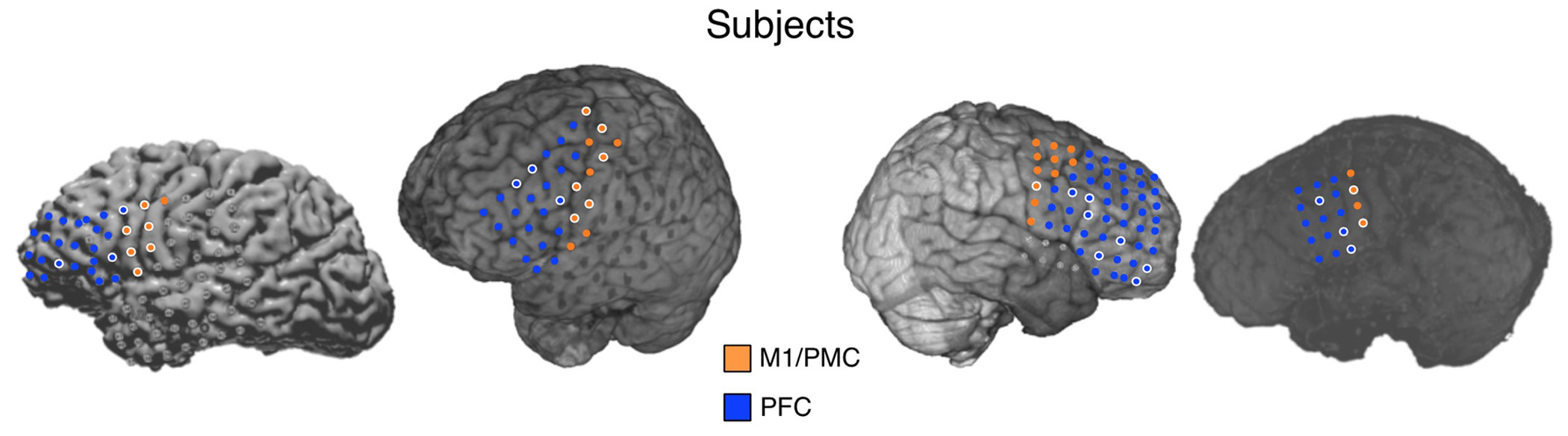

Because of the spatial limitations of ECoG--the electrodes are placed solely based on individual patient medical necessity--we were really only able to sub-divide the frontal lobes into two broad territories: pre/primary motor (M1/PMC) and prefrontal (PFC) cortices, as seen here:

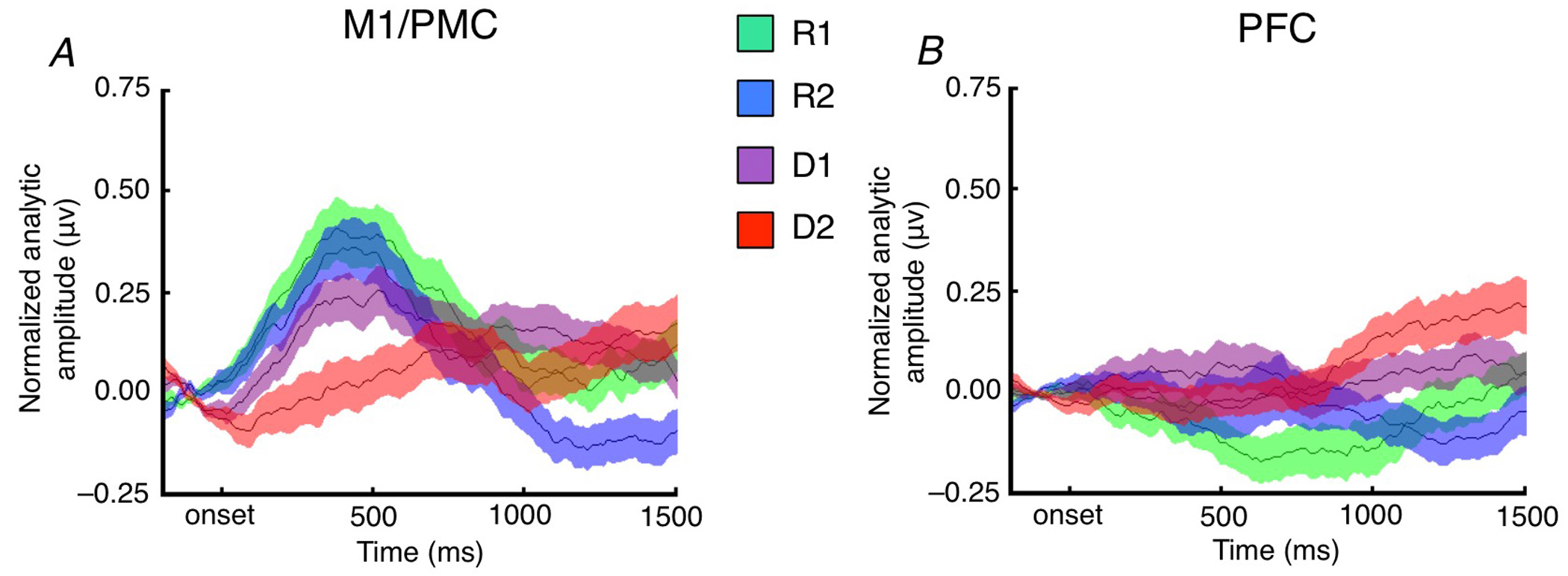

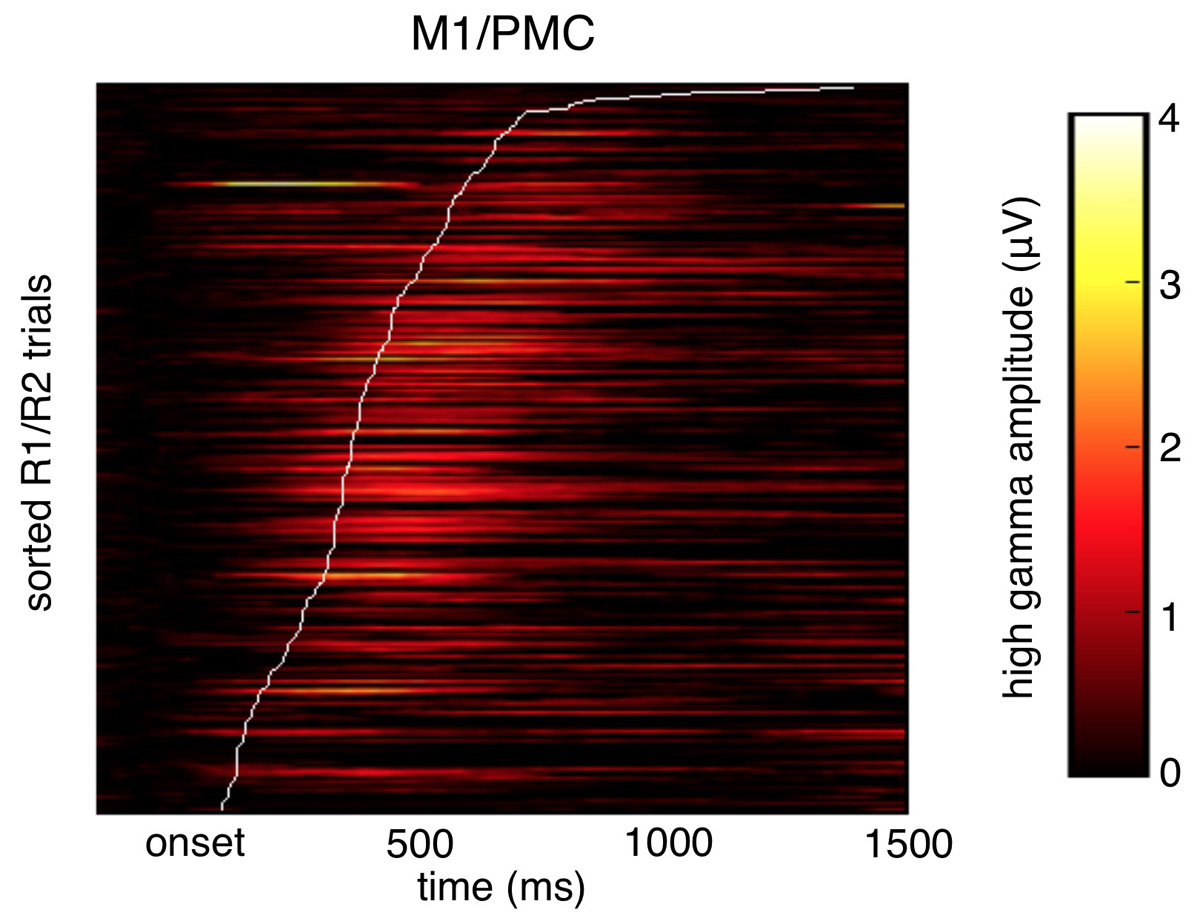

Here are the average high gamma time courses across each task condition, broken out by frontal sub-region, relative to stimulus onset (where R1 is simple stimulus/response and D2 is much more abstract):

(Note I'm glossing over a quite a few control analyses, etc. here and in what follows.)

This is essentially where the analyses were at by the time my first child was born, but the results left me feeling unfulfilled and full of questions:

- Why don't we see task-related increases in PFC high gamma?

- Isn't that PFC population doing something during this task?

- Why does PFC activity peak after M1/PMC activity?

Even more interesting was that if we regressed out the effect of the task, and just looked at residual response times controlling for task abstraction, we found that delays in PFC time-to-peak drive slower response times independent of task abstraction. Meaning trial-by-trial cortical "processing delays" slow responses.

As an aside here, because of the massive change in my post-parenthood lifestyle, I was spending a lot less time in the lab and a lot more time with my family, so a lot of the final analyses in this paper were run on my laptop, which got dragged around all over the place. For example, on vacation with the grandparents or on a solo road trip as I drove my cats and stuff down to San Diego for my move:

We know that PFC and M1/PMC are likely increasingly communicating with one another with increasing task abstraction, so how can I get measure that?

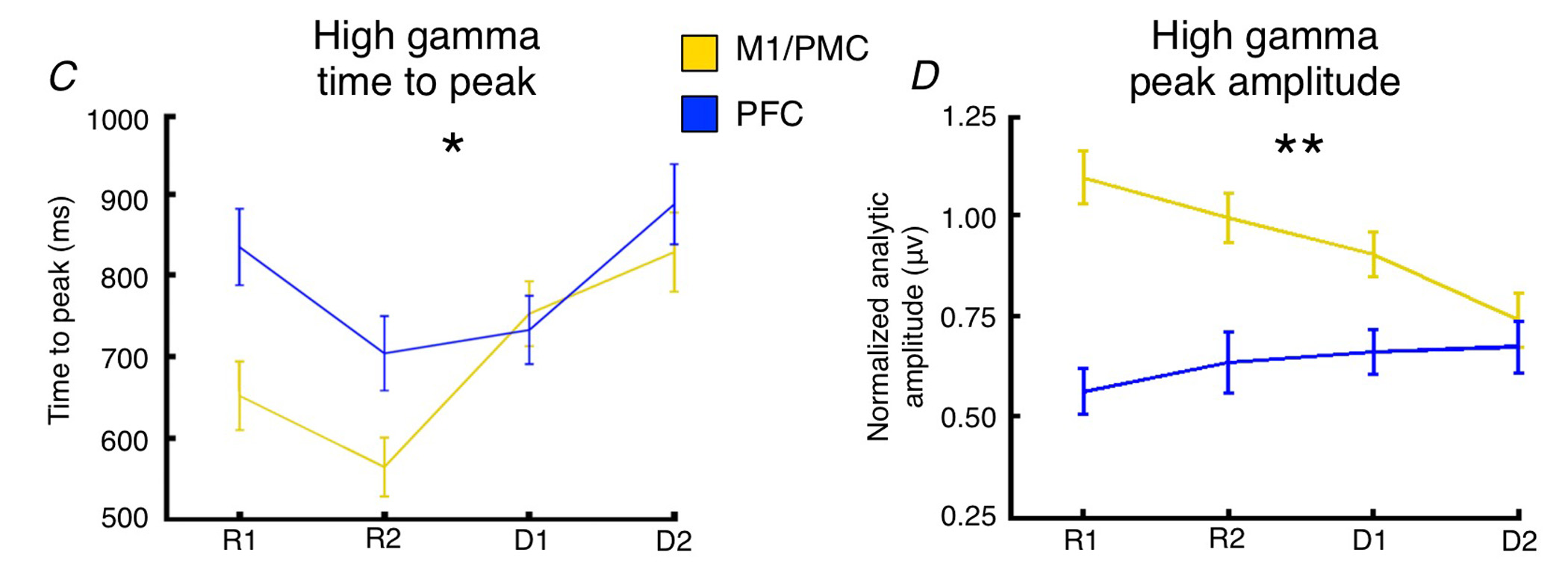

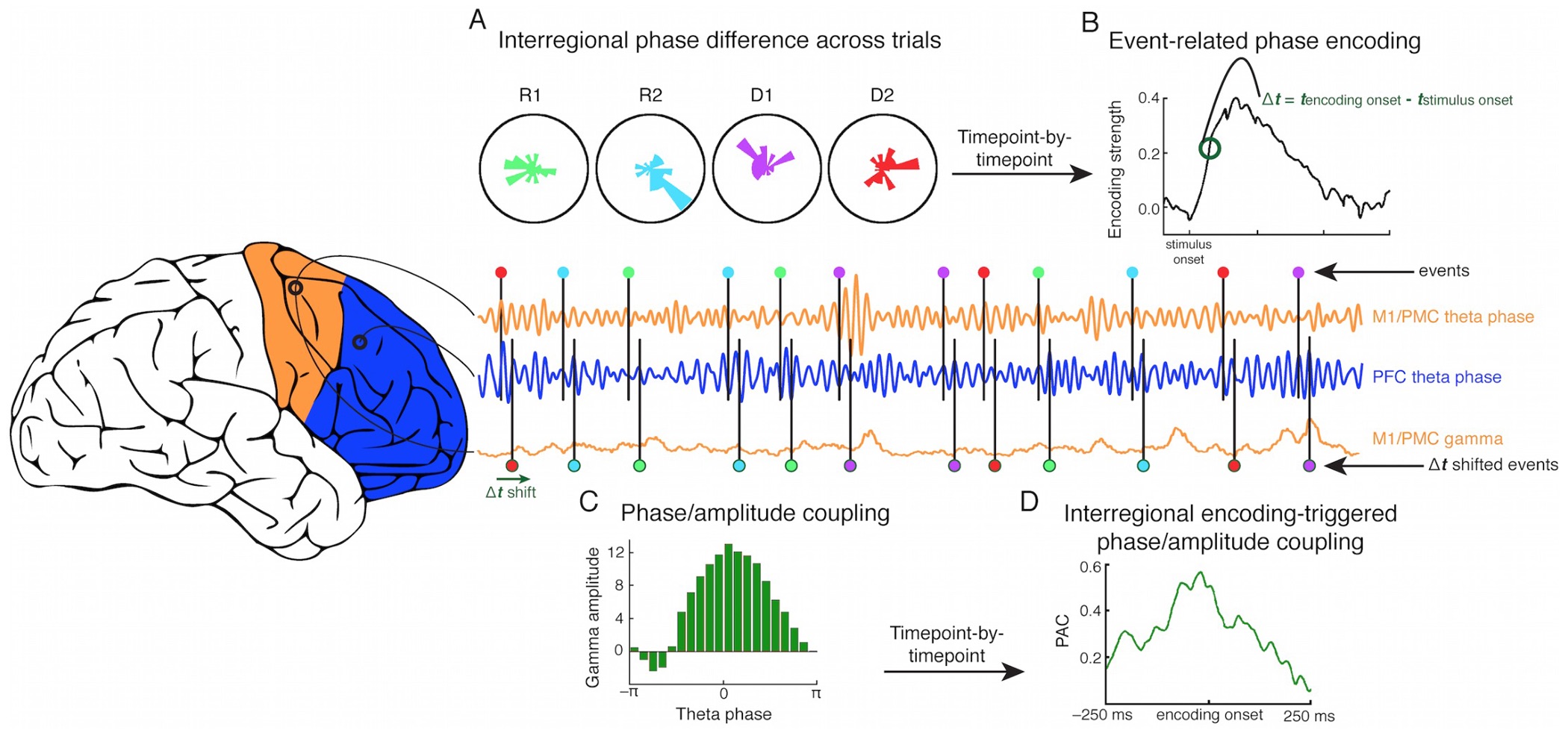

This resulted in what is my favorite published figure to date (originally made in crayon on a giant piece of paper, under the design guidance of my wife (and one-time co-author!) Jessica):

- Similar to the high gamma analyses, we can look at whether pairwise phase differences between all possible electrode pairs encodes information about the task (A).

- If a pair shows significant, sustained phase encoding, we can then see if that pair crosses between M1/PMC and PFC, or stays within either M1/PMC or within PFC.

- We find the exact millisecond when that encoding pair begins to encode task in their phase coupling (B).

- We then look at what high gamma activity is doing around that encoding moment, and whether pairwise phase differences predict high gamma amplitude (C and D).

- We can say, if the pair crosses between M1/PMC and PFC, we can look at whether M1/PMC phase is a better predictor of PFC high gamma, or vice versa.

What's funny is that my 2013 NeuroImage paper actually came about as I struggled with how to address the analytical issues I was running into for this paper.

So the idea here is that, as task abstraction increases, there should be increasing communication between PFC and M1/PFC, but because there's a lot of temporal variability in when this communication occurs, we need a way to account for that. Which is what Step 3 was designed to address, in the form of looking at oscillatory theta (4-8 Hz) activity.

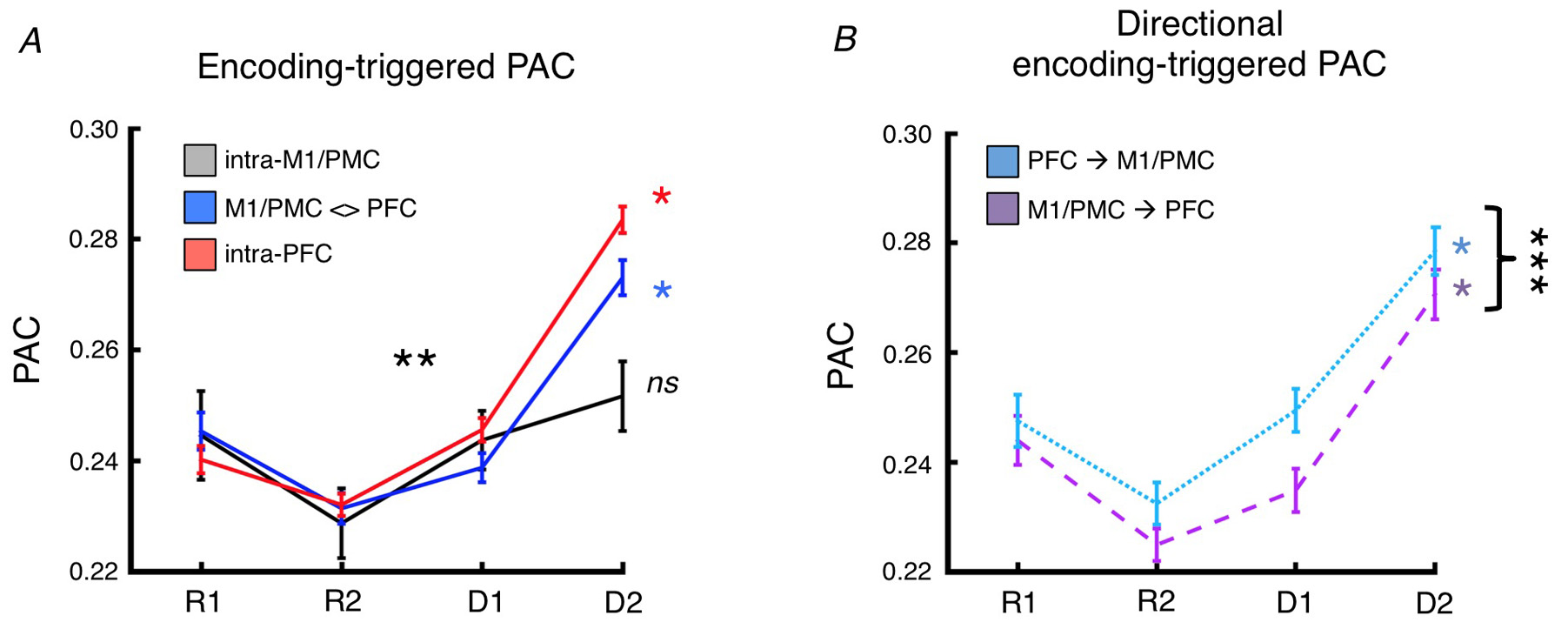

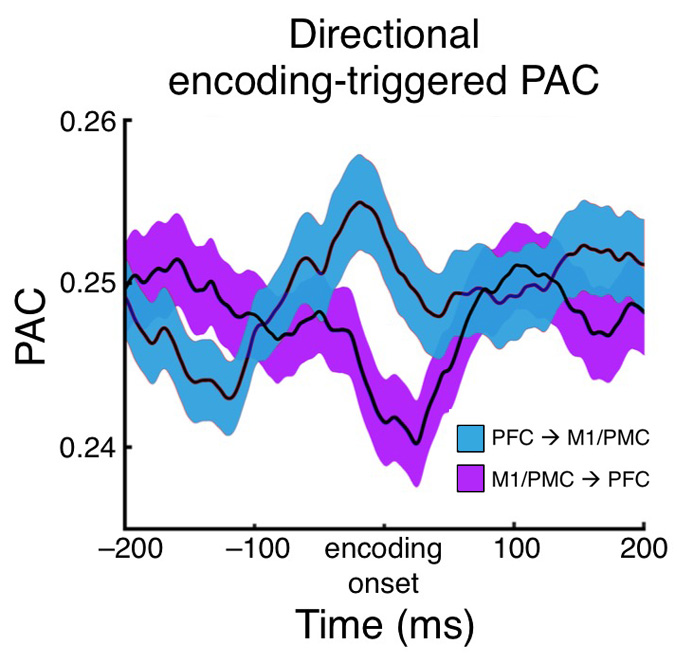

What we found was that with increasing task abstraction, theta phase to high gamma amplitude coupling around the time of inter-electrode phase encoding increased within the PFC, and well as between M1/PMC and PFC, but not within M1/PMC.

But the coolest thing was that for the inter-regional effect where phase encoding occurred between M1/PMC and PFC sites, there was also a directional effect such that PFC theta phase predicted M1/PMC high gamma stronger than M1/PMC phase predicted PFC high gamma. This makes sense from the view that PFC is "processing" the task goals and then "passing" that information to M1/PMC for motor response execution. Remember that all of these phase/amplitude coupling effects are relative specific to each electrode pairs' different encoding times. When we looked at this directional effect, for example, relative to stimulus onset instead, it disappears entirely.

Okay, so there are quite a few caveats here. This paper is far from perfect. Most notably, we're talking about effects seen across four people with epilepsy whose brains, by definition, have an electrophysiological pathology. Of course we couldn't get these data otherwise, and we take a great deal of care in not including in the analyses any electrodes that show epileptic activity, but there may be other more widespread electrophysiological changes affecting the results. The counter to that, however, is that these people are cognitively normal otherwise. Also the effect sizes here are pretty small: just a few percent of variance explained, or even less for the directionality analyses. To counter that though, this was truly our first-pass effort with limited data, new analysis methods designed to avoid false positives, and very limited spatial coverage. Also, such effect sizes are far from outside the norm in neurophysiology.

This all means that I have high hopes that as my lab starts digging in more, refining my crude attempts and challenging/improving on these assumptions, the science will quickly improve. And who knows, maybe this really is a tiny clue as to how in the heck our 86 billions or so neurons can possibly do any meaningful communication.

Voytek B, Kayser AS, Badre D, Fegen D, Chang EF, Crone NE, Parvizi J, Knight RT, & D'Esposito M (2015). Oscillatory dynamics coordinating human frontal networks in support of goal maintenance. Nature neuroscience PMID: 26214371