About Us

Our lab sits at the intersection of theory and experimentation, combining Cognitive Science, Neuroscience, and Data Science approaches:

- Cognitive Science: The study of intelligences, biological and artificial.

- Neuroscience: The study of the rules of biological neural networks and how they give rise to behavior and cognition.

- Data Science: The study of how we can combine many large, hetereogeneous, noisy datasets to derive knowledge about our world.

We care deeply about how we use data to learn about how the brain “works”: what are the functional/computational roles that neurons play in human cognition, aging, and disease? We do this from two complementary angles. From the experimental side, we conduct human cognitive experiments while recording either non-invasive electrical brain activity using EEG, or invasively by working with patients undergoing brain surgery (usually for epilepsy). We also collaborate extensively with researchers in a variety or other domains, and make considerable use of publicly available brain data (which we help catalog here).

We combine these experimental approaches with large scale data-mining, data science approaches, and AI/machine learning techniques to discover biological signals that are informative of cognitive and disease states.

From the computational side, we develop new methods for measuring and quantifying neural oscillations in both the time- and frequency domains (see our publications for our latest research). We also build models of neural circuitry to probe the computational capabilities of neural populations to investigate how oscillations impact computation and communication. Additionally, we model how these circuits contribute to the electrical brain signals we record. We validate these models by comparing to a wide range of electrophysiological data, including single-unit recordings and intracranial field potentials from humans and animals.

Ultimately, our research goal is to bridge these two approaches and construct an understanding of cognition built on the first principles of neurophysiology. Rather than asking questions like, “What brain regions correlate with working memory or attentional load?” we ask, “Given what we know about the computational properties of neurons and neural systems, how can those systems interact to give rise to cognitive phenomena we equate with ‘attention’ and ‘working memory’, and what are the behavioral and cognitive limitations and consequences of these biological constraints?”

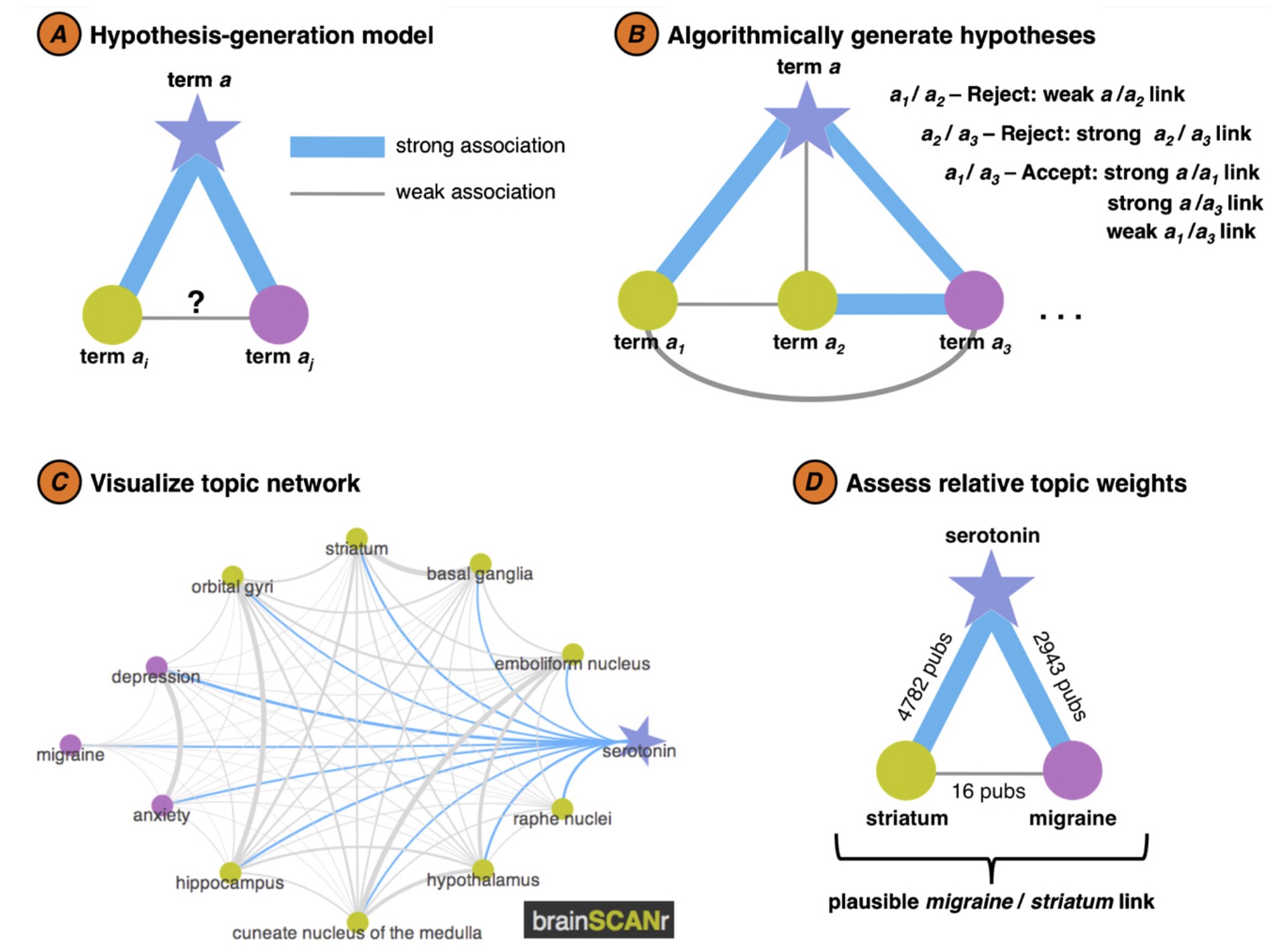

In collaboration with his wife, Jessica Bolger Voytek, Voytek built and published brainSCANr, an algorithmic approach to aggregating information from more than 2 million peer-reviewed neuroscience articles. This project was his first attempt at automated science: using machine-learning tools to algorithmically generate novel hypotheses from the text of peer-reviewed publicaitons alone. This is well before the days of large language models (LLMs). Our philosophy with regards to the role of data-driven approaches to neuroscience is that large scale data analytics can complement and guide in-lab experimental research, but should not replace it.