Neural Communication: Jazz, Not Symphony

May 28, 2015 by Bradley Voytek

(This is about my latest paper, "Dynamic Network Communication as a Unifying Neural Basis for Cognition, Development, Aging, and Disease." This paper was invited as part of a special issue for Biological Psychiatry titled "Cortical Oscillations for Cognitive/Circuit Dysfunction in Psychiatric Disorders," by the organizing editor, György Buzsáki. Although it was invited, it was still peer-reviewed as normal. This post originally appeared on the Forbes "Lab Bench" blog.)Although the idea of a “favorite” is somewhat fleeting (he is only three years old), one of my son’s go to nighttime reads is Beautiful Oops!, a colorful, inventive little children’s book by Barney Saltzberg. The appeal of this book is in how each page shows a different way one could turn an accident (a coffee stain on a page or a tear in a paper) into an opportunity for creative artistic expression.

The positive role that mistakes play in our lives has long been remarked upon, with Oscar Wilde quipping that, "experience is the name everyone gives to their mistakes." DJ Shadow talks about some of Public Enemy’s sampling work as a "collage of mistakes that in itself makes… a brilliant moment in music." These kinds of sampling errors and glitches are becoming more popular now, but even with that, few musical styles embrace mistakes like jazz musicians. "Do not fear mistakes," Jazz great Miles Davis said. "There are none."

The utility of mistakes isn't limited to art. What is evolution if not billions of years’ worth of beautiful oopses? Every little mutation is a mistake — an error in the replication of DNA. These errors are incredibly rare. Most of them have little to no biological effect; fewer are harmful; and fewer still are helpful. But in the same way a slip of a chord during a jazz improvisation can give rise to a brilliant interlude, these incredibly unlikely little twists of DNA are what gave rise to the amazing variety and abundance of life and experience of our world.

The human brain is an incredible product of the accumulation of countless generations of tiny genetic errors. The fact that the our 86 billion or so neurons (brain cells) inside our heads can communicate with one another in any meaningful way is the great mystery of neuroscience. This massive communication network is frequently likened to a “symphony… happening at the speed of thought,” as NIH Director Dr. Francis Collins recently put it. But this analogy is problematic, and led neuroscientist Wolf Singer to call the brain “an orchestra without a conductor.” The reason why the analogy is problematic is because neural communication is a chaotic mess. There is no orchestration, no clean melodies, no set tempo. Neurons send signals thousands of times per minute, many of which seem like noise to those of us recording their microscopic musical beats.

This very conundrum - how does the brain coordinate its own neural communication in such a chaotic, noisy, electrochemical environment? - is what drives the focus of my research in my lab at UC San Diego. Recently I wrote a paper with my colleague and UC Berkeley neuroscientist Robert Knight, trying to tackle this idea. Before I go into the details I want to preface this with a caveat: despite what cop procedurals and popular books would have you believe, we neuroscientists know very little about how the brain actually works and so the theories presented just represent the beginning of understanding how it works. As a result, these ideas are probably not 100% correct, but I’d like to think they’re less wrong than how we normally think of the brain.

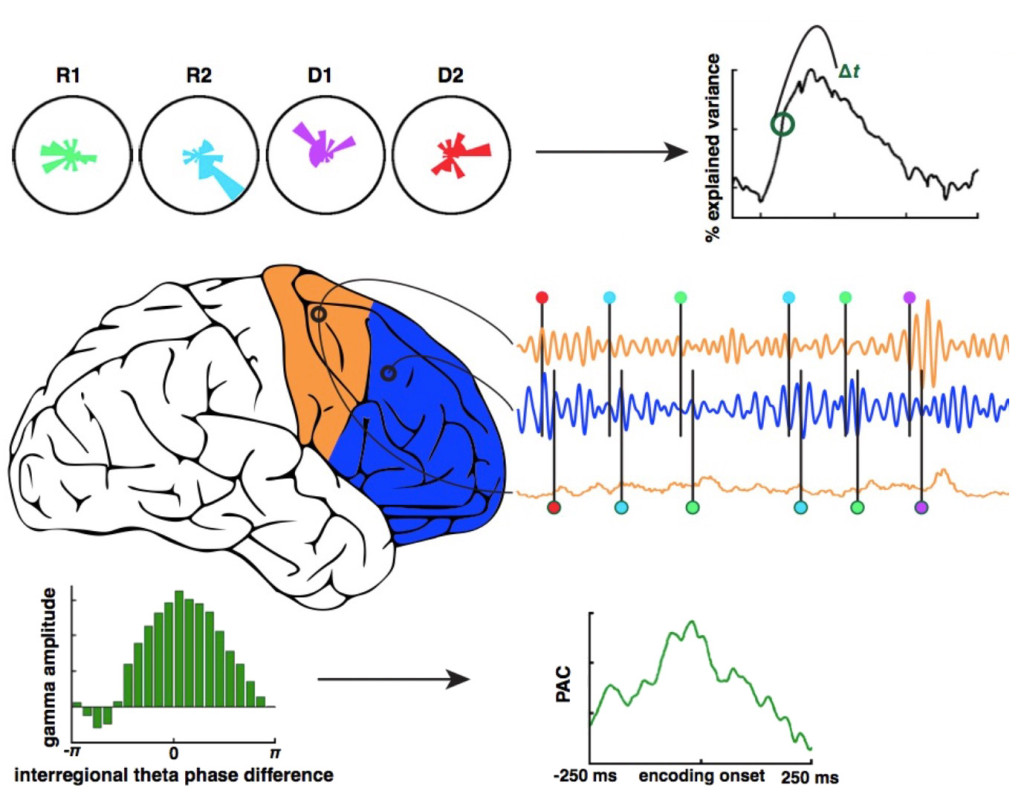

Embedded within the brain's electrochemical neural noise is something like a rhythm (and if you’re interested in more, I highly recommend the book Rhythms of the Brain by neuroscientist György Buzsáki). These neural rhythms take the form of oscillations (which you probably know as "brain waves"). While largely a mystery, we know that these oscillations play an important role in helping coordinate neurons in different brain regions by helping them synchronize their communication. Sort of like how the radio can sound like noise until you tune into a specific frequency, some of our neurons also seem to pay special attention to different brain rhythms. This theoretical view was is a boon to modern neuroscience, because it finally gave gives us something concrete to work with. It provided a model for how different parts of the brain can orchestrate their communications, absent a conductor.

This simple view — that brain rhythms are critical for coordinating communication in the brain — got disrupted when my colleagues Coralie de Hemptinne and Phil Starr from UC San Francisco published two papers showing that patients with Parkinson’s Disease have abnormally strong oscillatory coupling. They very clearly found that when these patients are implanted with a deep brain stimulator (DBS), the symptoms of their Parkinson’s disease improved while the coupling of these oscillations dissipated.

This left us with several questions that needed answering: 1) If this oscillatory coupling is a critical component of the brain’s communication code, why is Parkinson’s associated with movement problems? 2) Why does making the oscillations weaker with a DBS help so much? Shouldn’t shutting down this communication system be bad? 3) How does a DBS work? Because despite nearly 20 years of FDA-approved use for movement disorders like Parkinson’s, we still don’t understand how it causes these oscillations to desynchronize or why it works in alleviating the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

As a bonus problem, DBS also has FDA approval for use in treating obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and may also have benefits for depression and anxiety. The brain areas stimulated in all of these cases are quite different, so why DBS works is a mystery.

That’s where our recently-published theory comes into play. Our argument is that while neural oscillations are important for neural communication, these oscillations can come to dominate the brain’s signal. In the extreme case this can lead to “hypersynchronization” of the brain’s neurons and, ultimately, seizures or other disorders. Accordingly, we argue that the brain needs a way to break apart this rhythm apart.

When the brain is operating normally, we think this happens with “noise”—neurons that fire out of synch—which helps disrupt the over-orchestrated synchrony. So if these "noise"-neurons stop working properly, you might get the pathologically strong oscillations like you see in Parkinson’s. So in this view, DBS, which is an injection of electrical current directly into the brain, may literally just be adding noise into the brain’s circuits to break apart the unwanted synchrony - like breakbeats in hip hop that originated from jazz stop-time.

This theory may also explain why DBS works for seemingly unrelated disorders such as OCD. In neuroscience we have a phrase: "fire together, wire together." This phrase encapsulates an amazing discovery in neuroscience, originally referred to as the Hebbian rule, and now called spike-timing-dependent plasticity, which roughly states that the more a neural circuit gets used, the stronger the connections in the circuit become. So in our view, in a disorder such as OCD there is a circuit in the brain that is hypersynchronized, leading to the obsessive behaviors. In this case, then, DBS injects noise into this circuit to help break it apart, loosening the grip of obsessive-compulsive behaviors.

To bring it back to jazz: the percussionist lays down the rhythm for everyone else to follow, just like the brain’s oscillations guide the neurons’ communication. But if that beat is too loud, it’s hard for the rest of the crew to do their own thing. They all get stuck following the beat of the drummer who won’t let up. Jazz is best when there’s a give and take balancing the beat and the exploration of notes. So what happens if the beat’s too weak and the rest of the notes of the group are too discordant?

That’s the second arm of our theory: just like hypersynchronization can happen when there's too little noise, neural communication can also be disrupted by having too much noise and not enough rhythm. How might that manifest? Conceptually, one could imagine that noisy communication in the brain could lead to memory problems, disordered thoughts, or other issues. Recent research has found that both autism and schizophrenia, for example, are associated with increased neural noise. These disorders have seemingly very different neural origins, but their symptoms can be captured by our simple framework.

Our view here is quite different from how neurological and psychiatric disorders are normally viewed. These disorders are often framed as "chemical imbalances." What we’re proposing is that, instead, they are fundamentally neural communication disorders, one cause of which—but not necessarily the only cause—might be a neurochemical imbalance. The benefit of this viewpoint is that it shifts treatment away from a medication-dominant view and embraces a multifaceted treatment view. Such a view incorporates medicine to treat the neurochemical aspects, therapy to treat the circuit overcoupling aspects, and perhaps even targeted electrical stimulation treatments to counteract the electrical communication aspects.

The scale of the problems we’re facing in trying to understand the brain is daunting. Testable, falsifiable theories like ours are few and far between. If my theory is wrong, which it almost certainly is, I hope it at least becomes a "beautiful oops" that can point the way to a better understanding of the brain.

Voytek, B., & Knight, R. (2015). Dynamic Network Communication as a Unifying Neural Basis for Cognition, Development, Aging, and Disease Biological Psychiatry, 77 (12), 1089-1097 DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.016