Teaching Data Science at Scale

July 14, 2017 by Bradley Voytek

A few weeks back I outlined our vision for Data Science at UC San Diego. A major part of that vision is to help define and shape the field. While one way we can do that is through direct research, the most impactful way (in my opinion) is through educating the students who follow our curriculum.In this post I'll share some of the things I learned this past quarter while teaching Cognitive Science 108—Data Science in Practice. In a follow up post I'll share some of the final projects submitted by my students.

This was the first-ever offering of this course, so I had to design it from the ground up. To add complexity, the enrollment was massive—403 students total!

Cogsci 108 - my new Data Science in Practice class. I think students are interested in Data Science here at @UCSanDiego... pic.twitter.com/DdGa2nHXVP

— Brad Voytek (@bradleyvoytek) April 3, 2017

Before I go any further, I need to thank several people. First is Lead TA and Voyteklab PhD student Tom Donoghue, who put an enormous amount of work into setting up and maintaining the course GitHub account, helping write and test the homeworks, putting together all the Section Materials (see below), and so on.

Additionally I want to thank my dear friends Kirstie Whitaker (Turing Institute Research Fellow and Mozilla Fellow for Science) and Chris Holdgraf (Berkeley Institute for Data Science Fellow). Both of them stayed with me in San Diego for a few days while I picked their brains on how best to set this up.

Finally, I want to thank the students, who all took a huge chance signing up for a new course and being guinea pigs while we worked out all the kinks.

Course Philosophy

As I said in the course Syllabus, the goal of my other class (Cognitive Science 9—Introduction to Data Science) was to give an appreciation for what can be done with data and where data can even lead you astray. In contrast, for COGS 108 I adopted the educational view that “sometimes the best way to learn something is by doing it,” or, more importantly as author Neil Gaiman says, “sometimes the best way to learn something is by doing it wrong and looking at what you did.”

I wanted to teach students the joys and frustrations of the practice of Data Science. We didn't dive deeply into the methods or proofs of machine learning, clustering, etc. on purpose. The reasons for that were :

- There are entire classes on pretty much each of the topics we covered if students want in-depth details (which I hope they do after taking this class!)

- Those classes are taught by true experts in each of those domains.

- My expertise is not machine learning, big data, etc. It is in knowledge discovery and data intuitions.

- I take an open view to learning: data literacy is critical for modern society, and I don’t believe learning these topics should be limited to only those who excel at math, computation, and so on.

Course Mechanics

I decided from day one to make all of my lectures publicly available via UC San Diego's podcast and videocasting system (here). Faults, bad jokes, mistakes, and all.

To handle the massive deluge of questions, we used Piazza. This let me, the TAs, the undergrad instructional assistants, and the other students help one another anonymously or otherwise.

During sections, Tom used the Software Carpentry/Data Carpentry sticky note method:

We give each learner two sticky notes of different colors, e.g., red and green. These can be held up for voting, but their real use is as status flags. If someone has completed an exercise and wants it checked, they put the green sticky note on their laptop; if they run into a problem and need help, the put up the red one. This is better than having people raise their hands because:This also allowed us to "deputize" students who had more experience, so they could potentially help students who were stuck at various points in the exercises. This act both increases our ability to teach, by focusing on bigger questions and issues rather than smaller technical ones, while also provided the "deputized" students experience in teaching.

- it’s more discreet (which means they’re more likely to actually do it),

- they can keep working while their flag is raised, and

- the instructor can quickly see from the front of the room what state the class is in.

For the first assignment we had each student create a GitHub account, make a pull request of Assignment 1, make the required simple changes, and then push their chsa

All homework assignments, as well as the final project, were done using Jupyter notebooks and graded using Jess Hamrick's nbgrader tools. The Jupyter toolkit included numpy, scipy, pandas, scikit-learn, patsy, beautifulsoup, and scrapy (among others).

I chose to use GitHub and Jupyter because:

- For many software and data science jobs, a person's GitHub account acts as their de facto resume, and;

- Jupyter notebooks are excellent for combining code, narrative text, images, and so on in one clear document. I wanted the students to think through each aspect of the data analysis workflow, including the background rationalization, methodological choices, and discussion of the outcomes.

Finally, using GitHub let us place a lot of extra materials for students to leverage, including code!

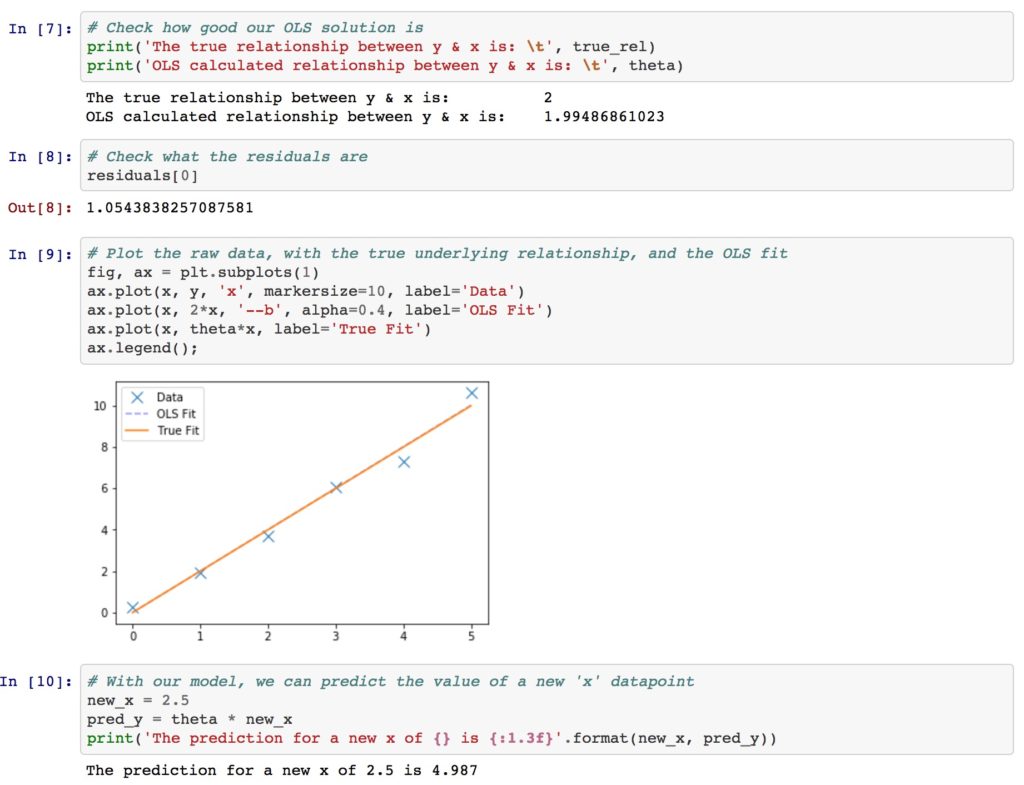

For example, in addition to the Assignments, we had Section Materials, which Tom put together to teach basic concepts and how to implement them in Python, such as this notebook on ordinary least squares (OLS):

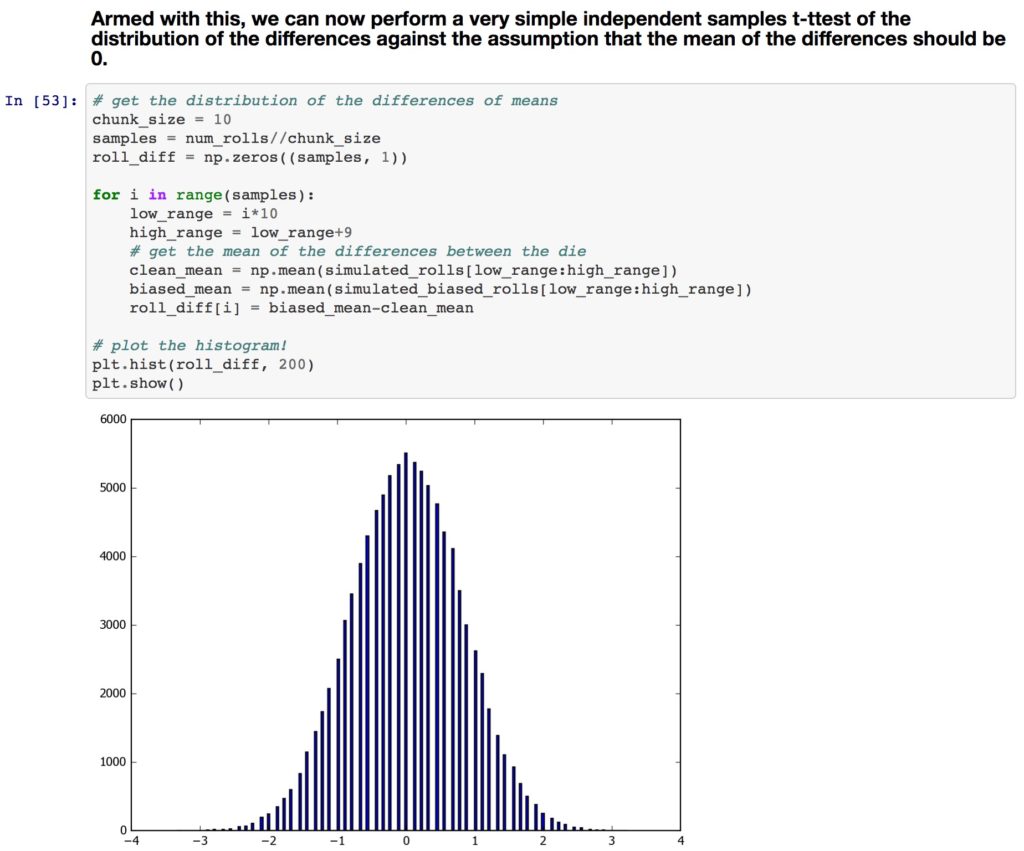

Or this walkthrough I put together to explain the utility of the Central Limit Theorem:

We had Lecture Materials, Workbooks, and Extra Materials to help students with things like Git.

Finally, to keep things interesting, I had a few guest lecturers, including UC San Diego professors Kamalika Chaudhuri from Computer Science and Eran Mukamel from Cognitive Science, as well as industry speakers Claire Dorman from Pandora Data Science and Matt White from Sony Data Science.

Hilarious data science presentation by @matthewmwhite for my Data Science in Practice class today. pic.twitter.com/RP8my3jfDh

— Brad Voytek (@bradleyvoytek) June 2, 2017

There were some things that worked, and some things that did not. And the students were savvy and picked up on that. For example, these two anonymous comments from my student evaluations nailed it:

The class only had one intro-level programming requirement, and it lead to a nearly bimodal distribution of number of study hours required. I heard over and again that Computer Science students were finishing assignments in 15 minutes while Cognitive Science students were taking 5-10 hours. That's too big of a spread, so as the Data Science curriculum here matures, we'll require an introduction to Python class.

- It seems like this class tried to bridge the experience gap between CS and COGS majors with regards to python, and desperately failed. As a CS major, the assignments were too easy, and yet many of those with no python experience struggled immensely. I'm not sure how this should be solved; perhaps have an introductory python course as a prerequisite which may also be fulfilled by a CS class?

- The class had a mix of Cogs, and CS students. (For the most part) Many felt it was too hard, and many felt it was too easy. It's hard to decide what direction the class should go. It was the perfect difficulty for me. It was hard enough to have the material be intellectually stimulating, and easy enough for me to not want to change my major and rethink life decisions. Good luck with improving the class. And thank you for offering this great class! It truly is what you make of it.

That said, I'm not beating myself up too much, as the comments from the students were constructive (showing they cared!) and also very much motivating for me to continue to put in the time and effort to build classes such as this one. Yes, I'm singing my own praises by posting the below comments, but they show that teaching Data Science at scale can work—and even be personal!—in a way they students really connect with:

In the next post, I'll show off the Final Projects the students put together!

- For first time teaching this class and there are not many Data Science in courses ANYWHERE kudos to Mr.Voytek. He maintains a relaxed demeanor even though I am sure it is very stressful. He is flexible in the course content even though we had a clear class guide at the beginning. I don't know any professors who could have handled it this well. Very approachable and has a clear passion.

- He is the best professor at UCSD. Going to his class always felt like a place where an instructor is truly in love what he does. Prof Voytek made me realize one should be happy at what they are doing. Thats what matters in the end - 'having a relationship with your work'.

- This course has really opened up Data Science as a possibility for my future. It's a fascinating field, and to hear Professor Voytek and the guest lecturers speak so passionately of it makes me really excited to participate.

- Professor Voytek is one of a kind, very generous, kind, and respectable. I wish most professors that taught here had the same enthusiasm as Voytek, I never had a professor that is just an overall great person like Voytek. The way he runs lectures and his overall class was great, it seemed very well-structured, organized, and not too challenging but not to easy as well. If i recall, this was also his first time teaching Cogs 108. I would say that Voytek showed us a great amount of topics needed for data science. I couldn't say much more other than Professor Voytek left me with an impression that there is still hope for ME and also OTHERS to do well, you can really tell that Voytek truly cares for his students to do well. If you're reading these evaluations professor Voytek, I want to truly thank you for everything that you were able to teach in the span of 10 weeks!