Teaching Neural Data Science

April 6, 2021 by Bradley Voytek

A few weeks ago marked the end of my first run of our new Neural Data Science course here at UC San Diego. This course was an experiment to see how far our undergraduate students could push at the boundaries of neuroscience, armed with a ton of publicly available data and new ways of thinking about how we can approach research.

In short: they absolutely exceeded my expectations—especially during the pandemic—and I’m pretty sure at least one peer-reviewed paper will come out of the research they did.

While I’m wildly excited to talk about those projects, I’m getting ahead of myself. I’ll post about the students’ projects over the next week, but first I want to begin with what I think Neural Data Science is?

For years now I’ve been arguing that Data Science is more than just (Computer Science) + (Statistics). I truly believe Data Science is something different. I’ve been slowly formalizing my thoughts on the matter, starting with two articles: The Virtuous Cycle of a Data Ecosystem (PLOS Computational Biology, 2016) and Social Media, Open Science, and Data Science Are Inextricably Linked (Neuron, 2017).

I summarize Neural Data Science with this:

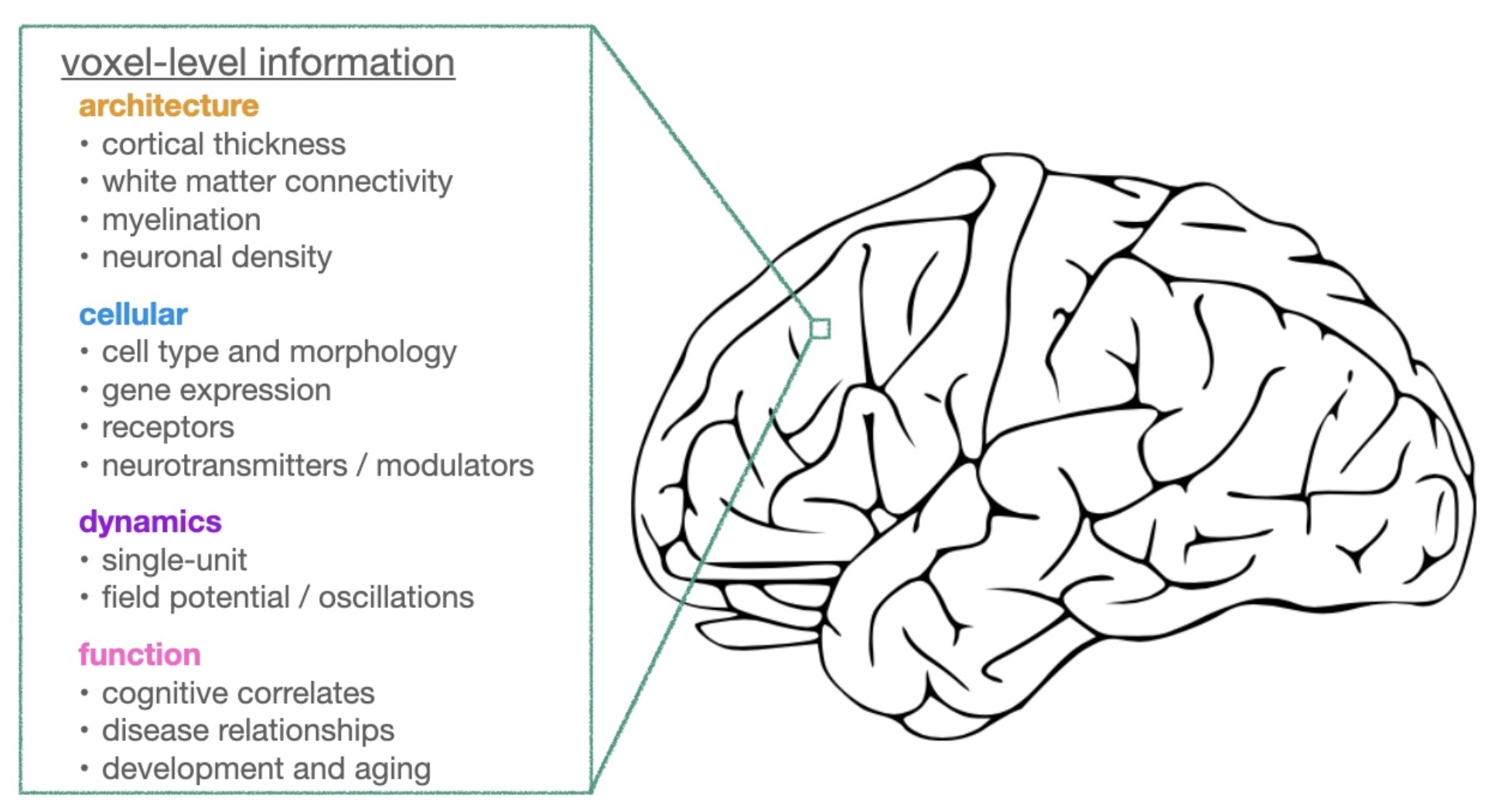

We know a lot about the brain. For any given arbitrary brain region, for example, there are thousands of studies describing its architecture: the thickness of the cortex, what its inputs and outputs are, myelination, cellular density, etc. We know about the cell types there and their morphology; as well as how strongly the 20,000 or so different genes are expressed in that region; what the receptor densities are; what neuro-transmitters / -modulators are present; and so on. We also have information about the electrophysiology of the cells in that region, as well as the macroscale field potential properties including aperiodic activity, oscillation frequency and waveform shape, and so on. Finally, we also have decades of human and animal studies hinting at what cognitive functions are associated with that region, how different diseases and disorders affect that region, and how all of these things change with development and aging.

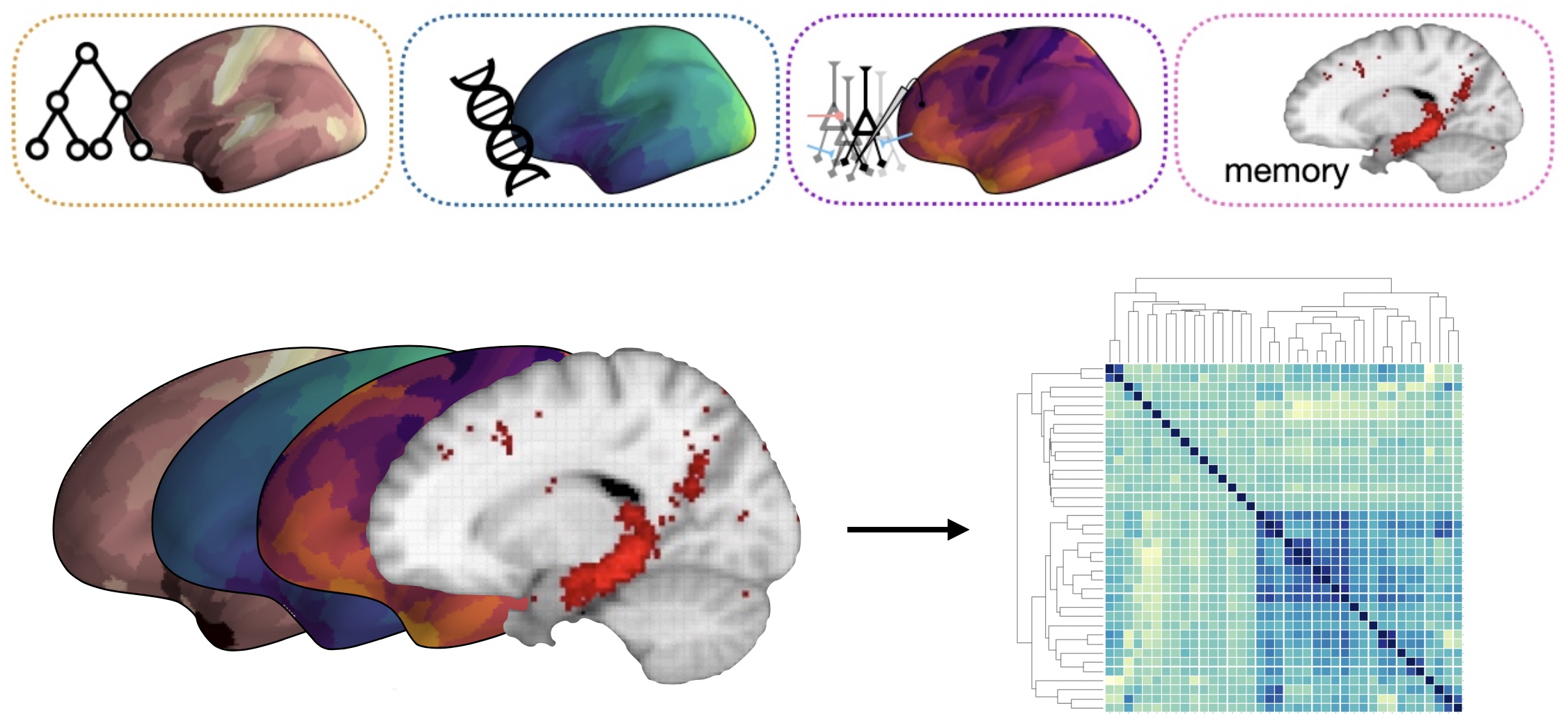

All of this information, however, is spread across tons of different datasets, papers, etc. Really amazing early data science projects, like Tal Yarkoni’s NeuroSynth, pioneered the mining these datasets to bring them together.

One of the goals of my group is to try and create methods and tools to allow people to more easily bring all of this information together. What if, instead of limiting ourselves to analyzing our one limited, biased set of data, we can also bolster our research with the huge amounts of other data that already exist?

This ethos can be seen in our recent paper, led by former PhD student Richard Gao, Neuronal timescales are functionally dynamic and shaped by cortical microarchitecture (eLife, 2020) where we combined theory and simulation with several open datasets, including:

- Human MRI data

- Several large dataset of human intracranial electrophysiology

- Human gene expression

- Non-human primate single-unit spiking

to show that we can infer population neuronal timescales from field potential / intracranial EEG data, and link the cortical topography of those timescales to brain structure and gene expression.

So when Ashley Juavinett and I started to brainstorm this course, we wanted to know if we could teach this kind of stuff to undergraduates. Now, certainly we’re not the only ones thinking about neural data science (Pascal Wallisch wrote a great book about his take!) Ours is simply a different perspective.

What if we could teach the next generation of neuroscientists to think from a “data first” perspective: what data would you need to answer your scientific questions of interest, without limitations on having to collect every piece of data yourself?

Here’s how I frame things in the course syllabus:

Neuroscience is a rapidly changing field that is increasingly moving towards ever larger and more diverse datasets that are analyzed using increasingly sophisticated computational and statistical methods. There is a strong need for neuroscientists who can think deeply about problems that incorporate information from a wide array of domains including psychology and behavior, cognitive science, genomics, pharmacology and chemistry, biophysics, statistics, and AI/ML. With its focus on combining many large, multidimensional, heterogeneous datasets to answer questions and solve problems, data science provides a framework for achieving this goal.

Determining what data one needs, and how to effectively combine datasets, is a creative process. For example, a neural data scientist might be tasked with combining: 1) demographic information and 2) multiple cognitive and behavioral measures, from people from whom we might collect; 3) biometric data, 4) motion capture data to understand motor control, and 5) eye-tracking to study attention, along with; 6) structural connectomic and 7) functional brain imaging data collected using methods with different spatial and temporal resolution (such as fMRI and EEG), and then place those results into context relative to; 8) average human brain gene expression patterns and 9) the existing knowledge embedded within the peer-reviewed neuroscience literature (>3,000,000 papers).

These types of data are very different: continuous and ordinal, time-series, video and images, directed graphs, spatial, high-dimensional categorical / nominal, and unstructured natural language. What is the appropriate way to aggregate and synthesize these data? What are the benefits and caveats for, say, aggregating spatially versus temporally? Being able to conceptualize how to carry out this integration is necessary before leveraging any technical skills will even be useful.

This focus in Data Science on creativity and integrating large, multidimensional, heterogeneous datasets is something Tom Donoghue, Shannon Ellis, and I really coalesced around in the Data Science in Practice course we created here at UC San Diego (a course that I’ve talked about on here before). We learned a lot from putting that course together, and wrote about that in our article, Teaching Creative and Practical Data Science at Scale (Journal of Statistics and Data Science Education, 2021)).

After the success of that course—which has 300-500 students every quarter now—it seemed like adapting that to neuroscience, specifically, made a lot of sense.

Before the quarter began, my Course Objectives were for the students to learn how to:

- think from a “data first” perspective: what data would you need to answer your scientific questions of interest?

- develop hypotheses specific to big data environments in neuroscience.

- work with many different neuroscience data types that might include data on brain structure and connectivity, single-unit spiking, field potential, gene expression, and even text-mining of the peer-reviewed neuroscientific literature.

- read and analyze data stored in standard formats (e.g., Neurodata Without Borders and Brain Imaging Data Structure).

- integrate multiple heterogeneous datasets in scientifically meaningful ways.

- choose statistical model(s) informed by the underlying data.

- design a big data experiment and excavate data from multiple open data sources.

- consider alternative hypotheses and assess for spurious correlations and results.

Certainly I didn’t meet all of these objectives. Adapting the course from my original vision to the pandemic-induced, online environment was imperfect, with one student calling the zoom-based project interactions “difficult” and “schizophrenic”. I was worried about how it all would “work”, but then there were comments like this:

I cannot speak highly enough about my experiences in this course and how well-prepared I feel for my continuing education at UCSD. This course’s material had significantly more personal connection and real-world application than other courses I have completed, and I am sure other students feel the same.

Seeing feedback like this, combined with the quality of the projects themselves, tells me that there’s something really cool and exciting here with Neural Data Science, and I can’t wait to teach it again and share more with you all.

In the meantime, you can look at the course materials on GitHub, here, and adapt them as you see fit. If you want to try and teach a version of this course, please let me know! I’d be happy to chat.